Before I move onto a discussion about protecting jewellery through patent law, I realise I didn’t quite finish discussion on design protection. I mentioned the UK 1839 Designs Registration Act but I should note that other countries introduced design laws to protect jewellery. In France, for instance, you might find a piece of jewellery stamped ‘Déposé’ which indicates that it is a registered design (see the stamp below). In Germany, you might see the stamp ‘Deponiert’ which means the same.

The 18th and 19th centuries saw significant advancements in inventions and technology associated with jewellery. Some jewellers preferred to keep their inventions secret while others began to use patents to protect their rights. Christopher Pinchbeck chose the former approach for protecting his gold substitute, pinchbeck, which he developed around 1720. Christopher died in 1732 and his son, Edward, inherited the business and the secret formula for pinchbeck. Edward Pinchbeck died in 1783 and supposedly the formula died with him but others attempted to copy the alloy. However, in the 1840s, electroplating of gold became available commercially and in 1854, legislation was enacted to allow for low carat gold such as 9ct to be used in jewellery and pinchbeck imitations began to lose favour.

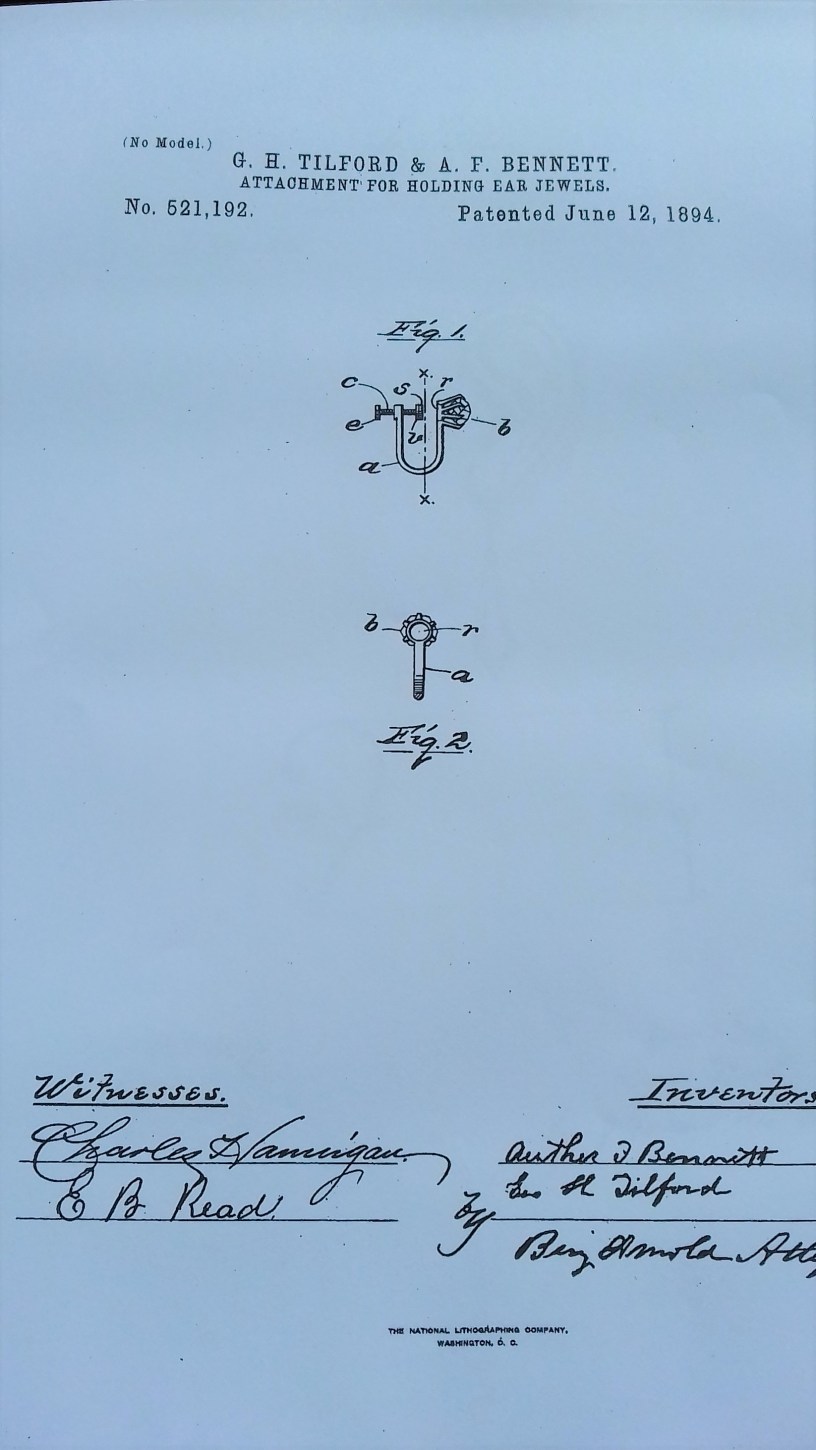

Patents began to be used to protect aspects of jewellery in the 18th century. A patent protects the development of a new and novel method of doing something. Staying with gold substitutes, the inventors of electro plating, George Elkington of Birmingham and his brother, filed a patent for electro plating in 1840.

A similar development to electroplating was rolled gold. At first, in 1795, the gold was soldered onto a sheet of brass and then the fused sheet was then rolled into a thin sheet. In 1817, John Turner of Birmingham was granted a patent for a new improvement in plating brass or copper with gold so that it could be rolled mechanically into sheets with jewellery pieces able to be stamped out. Instead of a solder, borax and silver were placed in between the gold and metal and then the piece was placed into a furnace to fuse the two sheets together. Sometimes the gold could be fused on both sides of the metal as is the case with the “Fix” rolled gold produced in France, by companies such as Murat, Fix, and Oria.

Another important patent was for vulcanite. Vulcanite was created from the heating of rubber and sulphur. Charles Goodyear patented a process for making soft, elastic rubber for use as a fabric in the US in 1844 and his brother, Nelson, patented a process for hard rubber in 1851. Thomas Hancock had also patented a similar process for vulcanisation of rubber in the UK in 1844, applying for it 8 weeks before Goodyear’s application.

Technology was also being used to produce chains. On the 2 February 1856, Bryce Grey Nichol from Rhode Island was granted a patent for ‘A new or improved method of manufacturing those kinds of ornamental metallic chains known as ‘Braxiliaa’ or ‘snake* and other like patterns’. In 1857, George Haseltine, a London patent lawyer, applied for a patent for a snake chain manufacturing process developed by E H Parry of Rhode Island. The machine was able to replace the work of seventy operatives and produce perfect snake chains. An improvement on this machine was patented in the UK in 1860. Patents for machines able to make other types of chains were granted in 1866, 1870, 1874 and 1875.

There are patents still being lodged today ranging from earring findings, bracelet clasps, expandable bracelets, and spring rings, and new iterations of older inventions keep occurring.

I will talk about copyright and trade marks in my next post.